Digital literacy as cultural approach

We are viewing a period of technological development that is both unprecedented and widely disruptive. In the short time since the Internet was created, much has changed, including the design of computer interfaces, the processing speed and portability of devices, the accessibility of information and knowledge, our methods of communication, the maintenance of our relationships, commerce, the protection of personal privacy, creative processes, publication of content, and the emergence of new digital tribes and virtual clans (Wheeler, 2009)1 .

Several recently published articles have explored the notion of ‘digital literacy’, and as expected, there are numerous views. Anderson (2010)2 for example, describes digital literacies as the ability to exploit the potential of computer technologies. Literacies, in all their forms, are at once cultural, social and personal (Kress, 2009)3 and enable us to interact fully in specific cultures. Some warn that without an adequate level of literacy, digital media have the capacity to disadvantage some (van Dijk, 2005)4, whilst others warn of the nature of the web to undermine knowledge and competency (Carr, 2008; Keen, 2007)5. However, the overwhelming majority of commentators eulogise over the potential of the social web to liberate education, and democratise learning, with the caveat that digital literacies are practiced. The American Library Association’s digital-literacy task force offers this definition: “Digital literacy is the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.”

The term “digital literacy” has become so popular and widespread over the last 10 years that it is almost taken for granted. With varying degrees of complexity, the phrase digital literacy is now used to describe our engagements with digital technologies as they mediate many (if not most) of our social interactions.

With this American Library Association digital literacy definition as a guiding light, it’s important to understand that even digital natives who know how to send a text and post to social media are not considered “digitally literate” by any means. It’s important to note that simply reading online or subscribing to an eBook service does not a digitally literate student make.

Digital literacy in education encompasses so much more. For example, you must have specific skills when reading online text that may contain embedded resources such as hyperlinks, audio clips, graphs, or charts that require you to make choices.

Digital literacy means having the skills you need to live, learn, and work in a society where communication and access to information is increasing through digital technologies like internet platform, social media, and mobile devices.

Developing your critical thinking is essential when you’re confronted with so much information in different formats – searching, sifting, evaluating, applying and producing information all require you to think critically.

Communication is also a key aspect of digital literacy. When communicating in virtual environments, the ability to clearly express your ideas, ask relevant questions, maintain respect, and build trust is just as important as when communicating in person.

You also need practical skills in using technology to access, manage, manipulate and create information in an ethical and sustainable way. It’s a continual learning process because of constant new apps and update and you need to keep your digital life in order!

Digital literacy is really important now and it will be really important in your professional future. In your workplace you are required to interact with people in digital environments, use information in appropriate ways, and create new ideas and products collaboratively. Above all, you need to maintain your digital identity and wellbeing as the digital landscape continues to change at a fast pace.

As mentioned, digital skills develop across a continuum, and they are constantly being updated in line with changes in technology. Digital skills frameworks serve a critical role in capturing the range of skills as well as these changes, thereby allowing policymakers and digital skills providers to ensure that their programmes and training curricula remain relevant and current. Many organizations and international agencies have developed digital skills frameworks. We highlight the work of the European Commission—the Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (or DigComp) that provides a common language on how to identify and describe the key areas of digital competence and thus offers a common reference at European level.6

Globally, the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) frames its benchmarks for digital literacy around six standards: creativity and innovation; communication and collaboration; research and information fluency; critical thinking, problem solving and decision making; digital citizenship; and technology operations and concepts.7

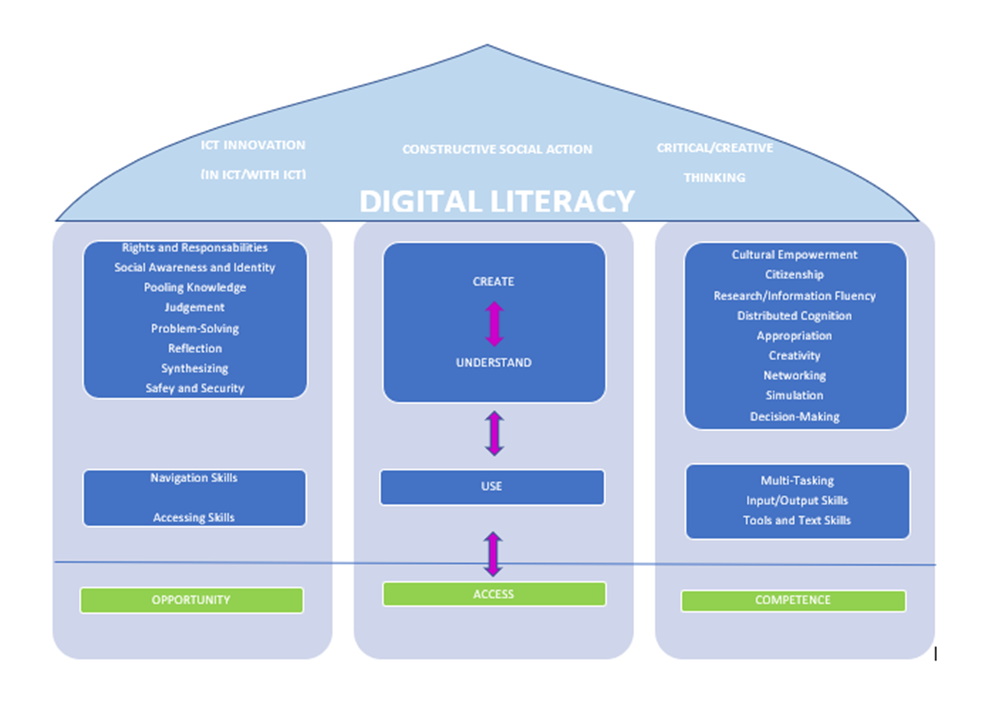

This model8 shows the many interconnected elements that fall under the digital literacy umbrella. There is a logical progression from the more fundamental skills towards the higher, more transformative levels, but doing so is not necessarily a sequential process: much depends on the needs of individual users, of your needs.

Digital Literacy Model

What are the elements that make you digitally literate?

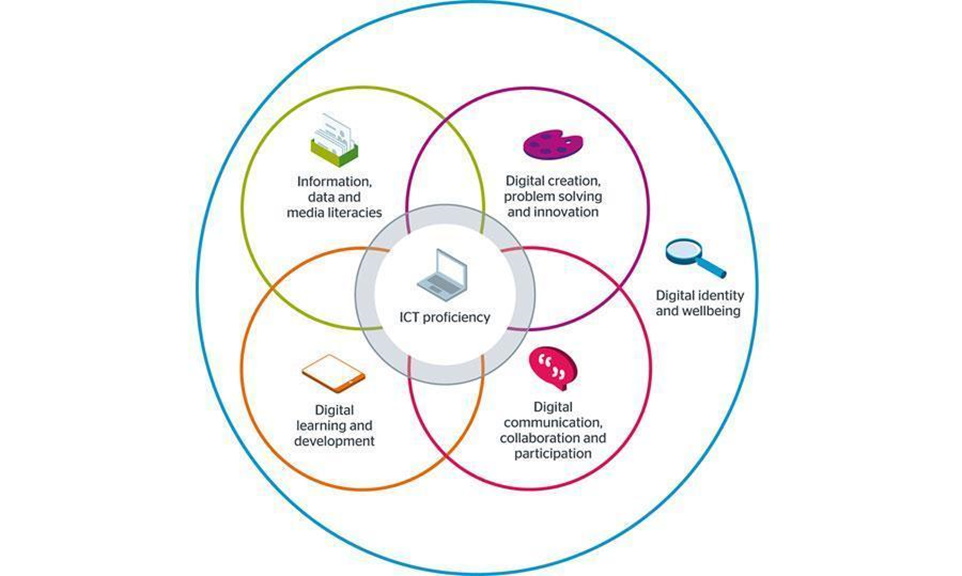

Digital literacy looks beyond functional IT skills to describe a richer set of digital behaviours, practices and identities.

The Jisc model9 below illustrates the idea that proficiency in ICT (Information and Communication Technology) is a core element in our digital literacy, whilst other skills overlap and build on this capability, and overarching it all is our digital identity and wellbeing.

The Jisc model

Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/building-digital-capability

- ICT proficiency (Functional skills)

- Information, data and media literacies (Critical use)

- Digital creation, problem solving and innovation (Creative production)

- Digital communication, collaboration and participation (Participation)

- Digital learning and development (Development)

- Digital identity and wellbeing (Self-actualising)

References

1 Wheeler, S. (2009, Ed) Connected Minds, Emerging Cultures: Cybercultures in Online Learning. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

2 Anderson, J. (2010) ICT Transforming Education: A Regional Guide. Bangkok: UNESCO Publication

3 Kress, G. (2009) Literacy in the New Media Age. Abingdon: Routledge.

4 Van Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide. Inequality in the Information Society. London: Sage Publications

5 Carr, N. (2008) Is Google Making us Stupid? The Atlantic, July/August Issue Retrieved May 21, 2012, from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/6868/#

Keen, A. (2007) The Cult of the Amateur: How Today’s Internet is Killing our Culture and Assaulting our Economy. London: Nicholas Brealey.

6 ‘[DigComp] is a tool to improve citizens’ digital competence, help policymakers formulate policies that support digital competence building, and plan education and training initiatives to improve the digital competence of specific target groups. DigComp also provides a common language on how to identify and describe the key areas of digital competence and thus offers a common reference at European level.’

7 International Society for Technology in Education (2007). iste.nets.s: Advancing Digital Age Learning. Iste.org/nets.

8 This figure is based on models from the Report of the Digital Britain Media Literacy Working Group. (March 2009), DigEuLit – a European Framework for Digital Literacy (2005), and Jenkins et al., (2006) Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century.

9 Jisc. (2016). Digital capabilities: The six elements.